| 1998 | Exposició "50 años de la muerte de Manolete" Casa de Madrid a Barcelona |

| 1989 | Exposició col.lectiva a la galeria Syra |

| 1982 | Coordinador / Participant a l'exposició presentada pel Reial Comité organitzador de la Copa Mundial de Futbol. |

|

|

|

|

| 1981 | Obté la Licenciatura de la Facultat de Belles Arts de Barcelona |

| 1969 | Beca “Borsa d'estudis d'escultura” a Perugia (Itàlia), otorgada per la “Dotació d'art Castellblanch” |

| 1968 | Obté el professorat de Dibuix. Imparteix classes a la Escola Superior de Bellas Arts |

| 1956 | Primera Medalla a l'Exposició Provincial d'Art |

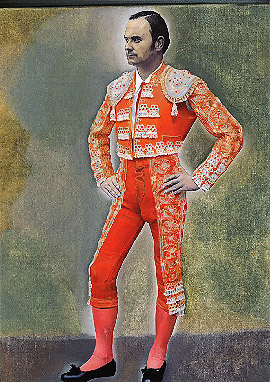

Llenç realitzat per Joan Matamala Flotats, quan l'artista Lluís Grau i Mestres

tenia uns 20 anys.

|

|

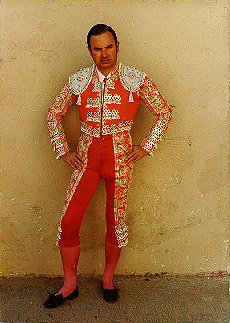

| El artista como torero. Fotografía |

El artista como torero. Pintura. 40,5 x 33 cm. |

“master, the bull is coming towards you!”

The relationship between the fine arts and bullfighting goes well beyond the names of those who have represented it in their works as artists. To name a few: Goya, Picasso, Rafael Durancamps, Manolo Hugue, Josep Granyer, Angel Ferrant, Fernando Botero, Ramon Lapyese, Eduardo Arranz-Bravo and amongst the younger ones, Miguel Macaya, Ramon Roig, XescoMerce and Antonio Tartas.

Needless to say, this list is actually more extensive. We need only look back in history and to the body of artistic works produced; for example, the cultures which deified the historical Egyptian bull Apsis (3000BC), converted the Cretan Minotaur into a myth and encapsulated it within the tangled labyrinth of Knossos, depicting it as a huge fighting bull on a rocky surface on the land of Guisando. Similarly, as hundreds of years previously, culminating in the 18th century, when bullfighters such as Costillares, Pepe Hillo or the great Pedro Romero, converted the rudimentary bullfights and cruel killings of wild bulls into some fundamental order, turning the fight into an art form.

Luis Grau is a bullfighter of this kind. He has been involved in the world of sculpture for more than fifty years: as a talented child and with precocious ease, he went naturally from being a student at Llotja School, (the historic Llotja which saw passing through its classrooms other talented and brilliant children such as Picasso), to being a teacher there, giving classes for more than thirty years. There he left evidence of his mastery and talent, always open to new developments, free forms and contents, both classic and contemporary. Various generations of students, some of whom today are renown artists, received his influences and that is without a doubt, always cause for pride. So much so that one could say that one of the main satisfactions which remain, after having being initiated into teaching, is to leave behind one’s mark and be able to carry on with other in depth investigations or “bullfights” of the artistic kind.

Therefore we see that Grau has left behind his mark only to take on new challenges: he not only never stopped investigating sculpture, running it parallel with his teaching, he never was subject to the constraints of his teaching practice. This has enabled him to focus on pure and unlimited creativity. He has not being subject to aesthetic canons or strict working hours or other imposed conditions.

This vital recent stage has also allowed him to disperse his efforts and concerns, not only in 3D or sculptured form (which has been mainly classical up to now on his artistic trajectory), but has allowed him to focus in areas such as painting, drawing and works related to the field of installations.

After having visited his studio, I was deeply surprised and profoundly moved: Grau, an artist with until recently little work because of his enormous sense of self-critique, pure bullfighter shame, showed me an ample body of work, the result of the last two to three years of activity. Through these same works, one could sense an outstanding magical

depth: they were works born from one’s interior, of beauty, simplicity, economy, of essence, of truth.

To reach this state, denotes our small achievements in sculptural works. We must feel in rather the same way as the bullfighter does, as the centre of attention, at the heart of the arena, where there exists constant risk, the pleasure of the true adventure, always composed of things which will come to an end and the certainty that that itself can be called capear- fighting the young bull.

This certainty is what experience gives us: of having fought in the arena, well or not, throughout time, in having always experienced the fear of the galloping bull coming towards us from the corral gate, almost without warning, yet having to apply the utmost steadfastness and command, each time with more and more elegance, class and conviction. Art is feared and loved as one loves a fighting bull. Each sculpture, once made manifest, once completed, spirit made form, now dies forever, as the bull must also die. The works from then on, beautiful skeletons of large fighting bulls, rest without their flesh, in our workplaces, in the homes of strangers and in museums. They remain in the artists’ memory as in the bullfighters’, whose job was well done, or as the reputation of a handsome bull who has made us triumphant. Surely for them, those beautiful works of art carry some sort of meaning.

In this sense it has to be said that in such complete works, as in a good bullfight., one could imagine metaphorical horns, which serve to remind us of that which before, was only a small bull with which we had to struggle constantly: we would struggle with composition, colour, form until we came up with an adequate solution, until we regain the homing instinct, then all fears of the bullfighter/artist vanish and the animal could be read and understood.

In this case and along the same lines, the presence of the animals’ spirits and that of the artist, the creator who gives form through the struggles, is doubly evident: at times we see the bull by it’s horns, literally described and at the same time clearly suggested through this interior gestation which characterizes aesthetic work, reductive and minimalist, typical of Grau. On other occasions, the points that stand out, the most sensitive parts, to be precise, of a large fighting bull, can be guessed at in these arenas, that Grau converts into metal circles, in wooden ellipses and in fine circles of baked clay.

Graus’ splendid pictorial works are made from a crushing synthesis; surfaces of raw linen are hardly outlined or drawn, the lines almost appearing accidental or haphazardly, with a chalk or Neanderthal carbon, with simple repetitive lines, in oil paint, pastel and papers on which simple, geometrical mystical forms and allegories have been pasted or stamped of the masters such as Grau at Llotja or Manolete at Alimon.

It is for this reason that I see in each version which Grau dedicates to the great bullfighter Manuel Rodriguez Sanchez, a little self-portrait. Not only because each work of art we create with our hands is a self portrait, but because Luis Grau himself is a torero, a bullfighter. It was his desire at a young age to actually be a bullfighter. He can be considered a bullfighter in the sense of being a creator who knows how to read between the lines: the beautiful metaphor of the art of bullfighting with the field of sculpture and the world of aesthetics.

For keen enthusiasts, from the universe of bullfighting and the universe of art, great works of art in both fields are always remembered. In this case, the one reveals the other, sheds light and clarity one to the other and they are both touched.

Therefore we can well say and permit me the license of the layperson, who knows nothing of bullfighting and only a little of the art of sculpture, “Master, the bull is coming towards you!”

Luís Casado

Translated by Julienne Onorato

July 2009

Structure and dynamism in the work of Grau Mstres

The first thing that one perceives of this world is not its forms but their energy. Their momentum is what defines them, their action characterizes them; being static has no meaning. At the most, being static would only be decorative, something which remains in the background in relation to what forms actually are.

As a consequence, there is no valid form which does not contain within it some sign of dynamism, force or action. In every form, there must contain within it, that which makes it possible.

Luis Grau Mestres is this sculptor, who sees in natural forms the verve that determines and characterizes them. For this reason, he has always preferred to dedicate himself to sculpting forms in which there is implicit in its action, forms of sportsmen and animals; from their simple figurative schemes they emanate their force and energy. In his musings to capture the forms of other models, the results of these approaches are figures that emanate energy, movement and action.

In this sense, one must say that his sculpture takes the tenets of Futurism as inspiration. It is a Futurism that could not conceive of forms as other than being dynamic; a fast moving car traveling at high speed is far more impressive than the static statue of the Venus of Milo itself.

In order to achieve this dynamic, Grau has no need to refer to the deformation of Futurism (those compositions based on successive cinematographic levels) but rather on the fact that the initial basic form extracts the original form of its own dynamics.

It is for this reason that it must be said that his sculpture is more closely related to Cubism than to Futurism; but of a Cubism which does not lend itself to a new type of construction on a physical reality plane of forms, but rather the type that captures the thrust inherent in them.

The dynamics of a bull lie in the silhouette formed by the horns; its strength emanates from its mass; the bullfighters’ silhouette determines his sharpness; his agility is the ability to compose in space that which occurs in time and lastly the monstrosity that resides within him. It is these five elements that are offered so that the artistic forms become reality and the essence of their influence.

This is the meaning of Grau’s work. It must be added that another important aspect of his work and concerns which determines the dynamics and energy of his sculptures is the material he employs to realize his works. It is these many facets in succession or coincidentally in time with which his forms are constructed. They are an organized synthesis which is revealed under the figurative presence.

Concomitant to his work as sculptor is that each form is initially seen as an architectural project as well as a chromatic presence. Colour forms part of the structure. Material, structure and chromatics are three elements closely related in the works of Grau. Yet, there is no material without colour, even if it is untouched, pristine or it has been applied. No material and no structure can exist without some sort of special architectural development or an active occupation and construction of this space.

His sculptures are herewith located, where oftentimes and simultaneously, their development is on a two dimensional plane as in that of painting. Sculpture, painting, architecture, dynamism, action and movement are the six factors that make up the ingredients of Grau’s work.

Sportsmen, bullfighters, animals and ordinary people, objects around which human activities are lived out ; these are the squares, cubes, ellipses and the characteristics pertaining to each of these forms acquires an active presence in the social contract, whether industrial or human, are what the artist gathers together. He synthesizes them, structures them, puts them together and brings them before our eyes. It is us as observers who have to be conscious that beneath each material, form, structure, montage and colour, there is a study of reality which the artist manifests in these works.

Simultaneously between them, these objects determine their surroundings and make up their own content. Grau does not conceive of any work which does not involve a vital interior, while at the same time, externalizing the complexity of each and every one of these things. In time and in each moment of each instant, there is development.

Arnau Puig, Art critic